Note: this was adapted from the advice I give to first-time TAs when they work with me in lecture classes. So it is probably most useful to those who haven’t taught a discussion section before. The advice isn’t revolutionary, but I hope it’s clear and usable.

Below is my advice for running an effective discussion session. There is no one teaching style that is ideal or even works for everyone, so adapt this as you see fit. These approaches have worked well for me, and at the very least can be a low-stress way to get through some of the first sections you teach. First is a section on teaching philosophy, which is my perspective on how to think about teaching. Then I have some specific methods I use in class. Finally, there’s an assorted list of short advice. If you find this useful or have any suggestions (or criticisms), I’d be excited to hear from you at jspecht[AT]nd.edu or on twitter.

Teaching Philosophy

- Teaching is about creating a community.

An effective classroom relies on creating a community out of the various people that show up for class. In a way, that community emerges organically, but you can do a lot to set the overall tone and shape how it evolves. Think about how to foster the kind of community that works for your students and you. That means, try to understand the type of students you have in class but also understand your own needs and perspective (see point #2).

- Everyone has a teaching identity/persona. Cultivate and understand yours.

Think about the kind of person you are (or want to be) in the classroom, how you come across, how you present yourself, how you engage with students. You can’t invent a persona but you can cultivate one within the limits of who you are as a person outside the classroom. Once you have a sense of that persona, the important thing is to consider the strengths/limits of your approach. For instance, the chill/fun professor might have engaged students but that can run at cross purposes with academic rigor (it also might be hard to become serious when the need arises). In contrast, the very serious professor might be initially intimidating (even if loved later). All teaching styles can and do work, but they all have their own strengths and weaknesses.

The final point on this is that some of one’s teaching persona depends on how students react to who you are. For example, this is striking in relation to gendered approaches to teaching, seeing how men can more often get away with the “cool professor” vibe. At the individual level, I’m not sure how to manage or solve that (and I’m not the right person to ask), but all of us should be sensitive to that dynamic and raise issues like students’ own assumptions/perceptions when asking students to complete evaluations (if you’re the kind of person with the ability to do so) and obviously remind colleagues who might not appreciate this point. If you have any thoughts about this, or think I’m addressing it clumsily, please let me know!

- Though you should strive to hone your teaching skills, successes or failures in the classroom are not a referendum on you as a person and are not even really exclusively about your teaching.

I once had a job where I taught four identical sections in a row. With only ten-minute breaks, it was a struggle to stay hydrated and fed during the course of that day. It did make the rest of my week much easier, but that’s a different conversation. The point is that I would teach the same section four times in a row and sometimes I’d leave a room and feel like the best teacher in the world. Then I’d do the same thing and it would fall totally flat. That was due to the particularities of the class, my energy levels, or the position of the planets or something. Other times a section would be amazing one week and the same class would be pretty “meh” the next.

Don’t let it get you down. Just focus on becoming a better teacher over time.

A related point: my first job had me teaching a ~100+ person class in my first semester at the institution. I had never had a classroom to myself before. The first week was…rough. But then it got better. I learned a lot about myself and about teaching. And by the end of the semester, I was much more effective. Teaching is a skill like any other and you can always get better.

General approaches

This is what has worked for me. You might find approaches that work better for you. What I like about the ideas below is that they allow both structure and flexibility, which makes your life a lot easier. That said, this is pretty traditional: it’s about a structured discussion of readings. It can be good to mix in activities (debates, roleplays, etc), and you’ll have to find ideas for those elsewhere!

- Consistency has benefits.

Students should develop a sense of how the section/discussion flows and how you’ll approach things. You should change it up occasionally to keep things fresh, but I find that giving students a sense of how things will generally work in class makes them comfortable and more willing to participate. For a more specific sense of what I mean by consistency, see points two and three.

- Over the course of a section, I like to move the discussion from big abstract themes to specific content discussion, back to big themes (broad -> narrow -> broad).

The idea is to first get them excited about the material, then force them to engage with it concretely (rather than rambling) and finally to think about the broader relevance/importance of what they’ve just read. This approach can also appeal to a variety of students, both the big picture thinkers and those that like to get in the weeds. If you notice, this structure also allows students to (1) reflect broadly, (2) present/find evidence for their views, and (3) think about the implications of these insights.

- Prime discussion by having small group discussion then whole class discussion.

Allow students to break into groups of four or so. I let them sit with friends and have the same groups each week if they want (I very occasionally randomize). They can be comfortable with friends and if you circulate, they will stay on task. Most importantly: give them specific things to do.

I usually give them three tasks: (1) A specific thing to find or discuss, (2) abstract idea to discuss, and (3) something like brainstorming themes of the text. Once they’ve discussed for ~7-10 minutes (and you should go around talking to them), you can bring them together for a collective discussion. The pump will be primed and you can cold-call students who had made good points while you were circulating. You can do this small group->big discussion process twice during section if you’d like, but more than that gets annoying for everyone involved.

General short tips

- Get advice from experienced teachers and if possible, watch other people teach or lead discussion sections.

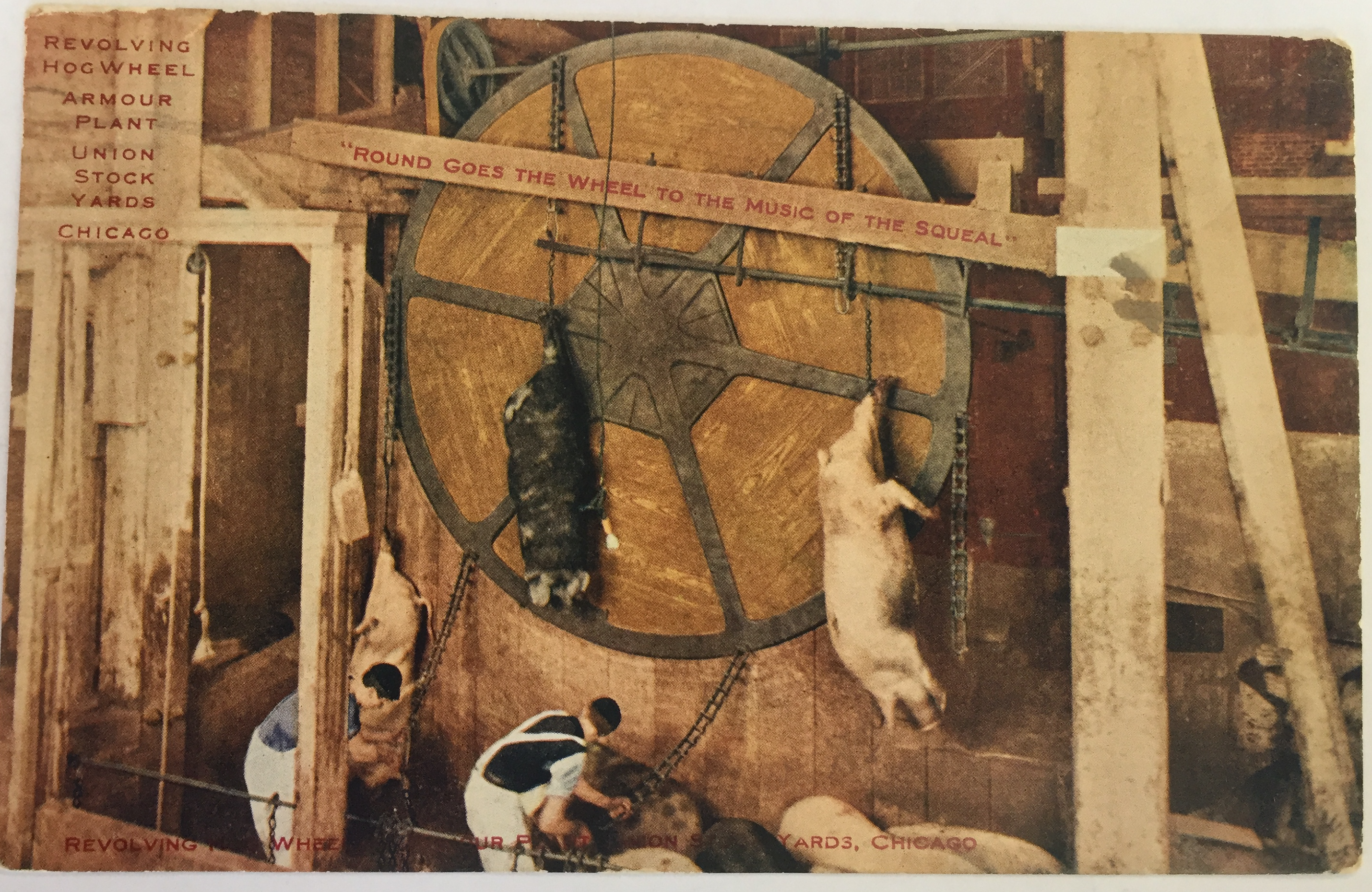

- Have emergency content as a backup to fill time: a very short primary source and an image (they love rambling about images) can be a life-saver.

- Use people’s names. This can be awkward at first, especially if you make a mistake, but you’ll learn the names quick.

- Circulate when students are in groups, you will get better at it.

- Have a plan for how you want section to go. It can be short or long, vague or detailed, but have one.

- Use the board. When you use it to get student feedback or ideas, whenever a student says something, write it on the board (or a translation of what they’re saying). If you’re too selective with what you put on the board, some students can get demoralized.

- Guide the students but don’t talk too much. At the end of section always do a gut check: did I talk too much? should I tone it down for the next one?

- If the students are quiet, you can sometimes just sit there and eventually they will crack. There is always someone who will crack. You don’t want it to always be you.

- Occasionally change things up in section. I either have a debate about the reading if its argumentative, some sort of mini-roleplay, or an unexpected primary source (visual, piece of music, etc.).

- Be sympathetic to your students, it’s hard out there.